I’ve been interested in logic for years, but have never taken the initiative to learn anything about the subject. Clark, my brother, suggested we go through a course on logic together as a remedy for our ignorance. As we journey through this course, I will post updates about what I’ve learned. The following notes are based off of the Critical Thinking lecture series presented by Dr. Greg Bahnsen.

LECTURE 1

Logic is the study of arguments. But what exactly is an argument?

An argument can be defined as a group of propositions where the truth of one is asserted on the basis of the evidence furnished by the others. Said more simply, an argument is a sequence of connected propositions that work together to support the truth of the ultimate proposition. The supporting propositions are known as the premises of the argument. The ultimate or final proposition (the point of the argument) is known as the conclusion.

Propositions, though, need to be more properly understood. A proposition is what a sentence asserts. It is either true or false. Questions and commands are not propositions.

A proposition is not unique to a specific sentence written in a specific language. Rather, a proposition is what that sentence asserts–it is the declarative sentence’s meaning. Thus, the same proposition can be expressed in a multitude of ways. Consider the following proposition: “In steady flight, an airplane’s lift is equal to its weight.” I could state the same proposition using a different sentence. For example: “An airplane’s weight is equal to its lift during steady flight.” The material sentences are different, but the immaterial proposition is the same. Aside: The existence of propositions is an importance concept in metaphysics. Metaphysics studies the nature of reality. Materialists believe that nothing immaterial exists. How can the existence of necessary abstract concepts like propositions logically abide in the materialist universe?

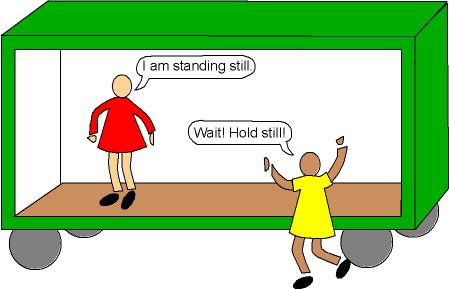

With this basic understanding of what propositions are and how they are used in arguments, it is now possible to introduce additional concepts that are used in the study of deductive arguments. An argument is said to be deductively valid when the conclusion cannot be false if the premises are true.

Stated differently, a valid argument has a conclusion that necessarily follows from the premises. A valid argument does not mean that the conclusion is true. It simply means the conclusion is true if the premises are true. To make this distinction clear, I’ve provided some examples below.

Example 1. Valid argument with a false conclusion.

Objects that are heavier than air cannot fly. Airplanes are heavier than air. Therefore, airplanes cannot fly.

Example 2. Valid argument with a true conclusion.

Airplanes can fly. A Cessna 182 is an airplane. Therefore, a Cessna 182 can fly.

Example 3. Invalid argument with a false conclusion.

Roses are red. Violets are blue. Therefore, Thomas is a woman.

Example 4. Invalid argument with a true conclusion.

Roses are red. Violets are blue. Therefore, Thomas is a man.

From the examples above, it is evident that both valid and invalid arguments can have either true or false conclusions. Validity’s only concern is whether the conclusion follows from the premises–not if the premises are true. Keep in mind that the concept of validity only applies to deductive arguments. Inductive arguments cannot be characterized using the concept of validity. The truth of the premises of an inductive argument does not necessitate the truth of the conclusion. The premises merely give some probability about the truth of the conclusion. With better information from the premises, the amount of uncertainty can be reduced, but never eliminated.

One more concept is needed to fully characterize an argument. This is the concept of soundness. An argument is sound if the premises are true and the argument is valid. Based on this definition, we know that sound arguments have true conclusions. I’ll use the tools of logic learned thus far to provide a sound argument in support of the statement that sound arguments have true conclusions.

Valid arguments cannot have false conclusions if the premises are true.

Sound arguments are valid arguments with true premises.

Therefore, a sound argument has a true conclusion.

In summary, logic is the study of arguments. An argument consists of related premises that drive towards a conclusion. Both premises and conclusions are propositions and all propositions are either true or false. An argument is valid when its conclusion cannot be false if the premises are true. An argument is either valid or invalid–not true or false. An argument is sound if the argument is valid and the premises are true. Sound argument always have true conclusions.